Dear Serial Readers,

There's a powerful tempo to these last numbers that I'm finding really compelling at a time with plenty of serious reading competition going on in my daily life! The three chapters of #18 provide that delicious tonal range, from the melodramatic and monomaniacal to the soothingly sentimental.

I've often commented on Dickens's verb-tense switching in DOMBEY. What I found especially astounding in chap 55 on Carker's mad flight from France back to England was the suspension of verb tenses altogether. I marveled here at Dickens's verbal (without verbs no less) brilliance, how his style beautifully captures the frenetic fugitive. Especially effective was the long section (pp 817-19, Oxford UP) of prepositional phrases starting with "of"--the possessive and compulsive syntax that conveys Carker's mental condition. Sections like these surely seem like a postmodern Dickens to me--a different strain of psychological realism than we get in Eliot's novels. While I wouldn't say that this chapter renders Carker a sympathetic character, still I'm fascinated by Dickens's adroit handling of Carker's frenzy, something that reveals the flipside of his otherwise iron-clad controlling nature that now drives himself rather than manipulates others.

This chapter anticipates a later Dickens monomaniac and his demise, namely Bradley Headstone. I'm sure other readers can think of more parallels, more doubles. And speaking of doubles, I thought the railway "monsters" provided a phantasmagoric touch, a frightening modern machine that Dickens seems to link with Carker and with Dombey at the end of the chapter. Here I thought of Frankenstein and his creature and their mutual pursuit and flight.

The other two chapters offer comic relief and softer tones, with the obvious contrast of Florence's wedding from not only the one briefly mentioned at the start of chap 57, but more pointedly from the earlier marriage between Dombey and Edith.

What do you make of Florence and Walter sailing away from England? What's the significance of this exodus, that their cross-class match can't be sustained in a traditional, class-bound, materialistic society? Since others here have mentioned Gwendolen and DANIEL DERONDA, I also thought of the ending of Eliot's later novel--only Daniel and his new bride don't set sail in the narrative, while this chapter ends with the newlyweds at sea, in the present tense of those whispering waves "not bounded by the confines of this world, or by the end of time."

Only one more number to go! In my ongoing commitment to "part-numberness," I won't divide my posts on this last double part-issue (#19-20, chaps 58-62). But I will likely take two weeks--and aim for Oct. 13th.

Remember that DROOD starts on a biweekly schedule on Monday Oct. 20th. The parts are shorter in length, and we'll take two weeks per number, and there are only six. Sign up via Mousehold Words (see link on sidebar of blog) and spread the word!

Serially yours,

Susan

POOR MISS FINCH by Wilkie Collins

29 September 2008

21 September 2008

Dombey #17 (chaps 52-54) February 1848

Dear Serial Reader(s),

We've been dwindling in commenting numbers these weeks. I wonder if you noticed that I didn't deliver a post last week? I'd like to claim that the boat carrying the part-issue numbers just didn't arrive, although I waited eagerly (wanting to know about the elopement of Edith and Carker) for hours and days. Yes, there was a delivery problem last week--between the pages and my eyes. But we're also nearing the end of this novel, and approaching a new serial reading adventure next month where I'm hoping that the shorter length of Drood (along with the delivery system of Mousehold Words--see sidebar) will increase our community of serial readers. Please do spread the word about the coming attraction.

So a few thoughts on this installment: a cleverly structured number with various groups trying to gather information about the shocking elopement of Edith and Carker in the first two chapters as a fine accretion of suspense leading to the last chapter where we finally see Edith and Carker in DIJON. I love the self-conscious construction and delivery of this "intelligence" of the elopement via Carker's variously abused associates throughout the number.

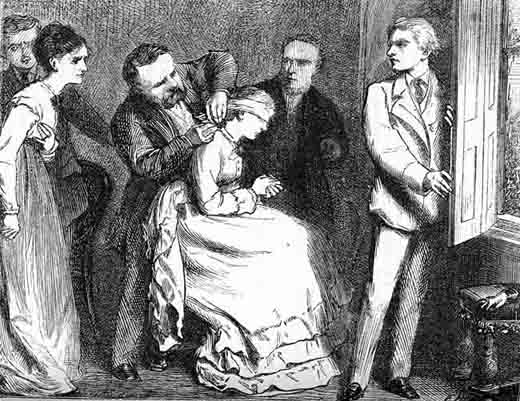

I'm also continually taken with the emphasis on maligned, abused, and furious women. Alice tells Harriet the story of Carker seducing and discarding her, a companion narrative to Edith's marriage market and elopement plot accounts. Alice's story reminded me of Esther Barton in Gaskell's novel of the same year this episode appeared. Then in the last chapter here, Edith delivers a powerful "I am a woman" speech to Carker in their Dijon quarters in which she echoes some of Alice's murderous sentiments, and we have the illustration to emphasize her imperial stature in contrast to his slimy and now cowering posture. Does this section redeem Edith from the sexual taint of the elopement? But this long delivery has another purpose, to fill in the narrative gap of the elopement plot from a few numbers ago.

More than earlier installments, these last few seem especially designed to get readers to read on, to discover what happens. Will Dombey murder Carker in this revenge plot where he's been set up as the proxy for at least two or even three wronged and furious women? Will Edith persist in turning her passionate anger toward herself? I suspect there are more deaths in store, of a very different tonality than Paul's sentimental death, or Mrs. Skewton's (aka Cleopatra) sardonic death, or even Walter's falsely reported death.

I'd wager that we don't get Dombey and Carker and Edith next time, since the pattern is usually a detour installment to build more craving for resolution. What's up with Florence, Walter, Cuttle, and will Old Sol return?

Next time: #18, chapters 55-57.

In serial time,

Susan

We've been dwindling in commenting numbers these weeks. I wonder if you noticed that I didn't deliver a post last week? I'd like to claim that the boat carrying the part-issue numbers just didn't arrive, although I waited eagerly (wanting to know about the elopement of Edith and Carker) for hours and days. Yes, there was a delivery problem last week--between the pages and my eyes. But we're also nearing the end of this novel, and approaching a new serial reading adventure next month where I'm hoping that the shorter length of Drood (along with the delivery system of Mousehold Words--see sidebar) will increase our community of serial readers. Please do spread the word about the coming attraction.

So a few thoughts on this installment: a cleverly structured number with various groups trying to gather information about the shocking elopement of Edith and Carker in the first two chapters as a fine accretion of suspense leading to the last chapter where we finally see Edith and Carker in DIJON. I love the self-conscious construction and delivery of this "intelligence" of the elopement via Carker's variously abused associates throughout the number.

I'm also continually taken with the emphasis on maligned, abused, and furious women. Alice tells Harriet the story of Carker seducing and discarding her, a companion narrative to Edith's marriage market and elopement plot accounts. Alice's story reminded me of Esther Barton in Gaskell's novel of the same year this episode appeared. Then in the last chapter here, Edith delivers a powerful "I am a woman" speech to Carker in their Dijon quarters in which she echoes some of Alice's murderous sentiments, and we have the illustration to emphasize her imperial stature in contrast to his slimy and now cowering posture. Does this section redeem Edith from the sexual taint of the elopement? But this long delivery has another purpose, to fill in the narrative gap of the elopement plot from a few numbers ago.

More than earlier installments, these last few seem especially designed to get readers to read on, to discover what happens. Will Dombey murder Carker in this revenge plot where he's been set up as the proxy for at least two or even three wronged and furious women? Will Edith persist in turning her passionate anger toward herself? I suspect there are more deaths in store, of a very different tonality than Paul's sentimental death, or Mrs. Skewton's (aka Cleopatra) sardonic death, or even Walter's falsely reported death.

I'd wager that we don't get Dombey and Carker and Edith next time, since the pattern is usually a detour installment to build more craving for resolution. What's up with Florence, Walter, Cuttle, and will Old Sol return?

Next time: #18, chapters 55-57.

In serial time,

Susan

08 September 2008

Dombey #16 (chaps 49-51) January 1848

Dear Serial Readers,

Happy New Year! I mean, of course, January 1848, when the sixteenth installment first appeared, but for many of us serial readers, it is also the start of a new academic year. Like others, my comments will be brief here. Still, I'd like to continue on track, since we're so close to the end of the novel. I don't think I can manage reading the double-number (19-20) of the last installment in one week though, so I propose we take a week for each one. This means: #17 for Sept 15, #18 for Sept 22, #19 for Sept 29, and #20 for Oct 6. I also propose that we next turn to The Mystery of Edwin Drood for two reasons: only six parts and available for delivery via Mousehold Words. You can subscribe through Mousehold Words and have each part number delivered to you electronically on whatever schedule you request. Even if you prefer to read the novel in book form, these deliveries will serve as reminders, and simulate (virtually, of course) the part-issue publications for Dickens's original readers. I recommend a biweekly plan for Drood, beginning on Monday Oct. 20. We would then finish just around a different new year.

After the calamities of the last number, #16 delivers a generous heaping of Dickensian sentiment. Florence has lost her home and father (although I found some relief that she finally fled a "corner" house in which any semblance of family and home had withered and died), and now she finds a home of genuine solicitude and warmth. Where Dickens introduced a working-class angel into the middle-class Dombey household in number #1 through Richards, here he relocates his middle-class angel into a modest, East London, sea captain's home and shop. On Walter's somewhat anticipated return from the deep: I was interested that we don't actually get details on how Walter survived a shipwreck, and what we do get is conveyed in Cuttle's bare-bones story which serves to clue-in Florence to Walter's appearance, first through the illustrated shadow on the wall. I'm interested also in another reversal: Florence's proposal to Walter. Presumably her superior class station trumps gender here.

The final chapter, back at the Dombey domicile, marks this scene and tone shift with the use of the present tense, and with wry narratorial addresses, something we've seen often in the novel. The concluding line, "Mr Dombey and the world are alone together," accentuates the ironic treatment of solitude and isolation we've commented on.

Next week: #17, chaps. 52-54.

Please spread the word about Drood and "Mousehold Words"--every other week starting mid October!

Yours in seriality,

Susan

Happy New Year! I mean, of course, January 1848, when the sixteenth installment first appeared, but for many of us serial readers, it is also the start of a new academic year. Like others, my comments will be brief here. Still, I'd like to continue on track, since we're so close to the end of the novel. I don't think I can manage reading the double-number (19-20) of the last installment in one week though, so I propose we take a week for each one. This means: #17 for Sept 15, #18 for Sept 22, #19 for Sept 29, and #20 for Oct 6. I also propose that we next turn to The Mystery of Edwin Drood for two reasons: only six parts and available for delivery via Mousehold Words. You can subscribe through Mousehold Words and have each part number delivered to you electronically on whatever schedule you request. Even if you prefer to read the novel in book form, these deliveries will serve as reminders, and simulate (virtually, of course) the part-issue publications for Dickens's original readers. I recommend a biweekly plan for Drood, beginning on Monday Oct. 20. We would then finish just around a different new year.

After the calamities of the last number, #16 delivers a generous heaping of Dickensian sentiment. Florence has lost her home and father (although I found some relief that she finally fled a "corner" house in which any semblance of family and home had withered and died), and now she finds a home of genuine solicitude and warmth. Where Dickens introduced a working-class angel into the middle-class Dombey household in number #1 through Richards, here he relocates his middle-class angel into a modest, East London, sea captain's home and shop. On Walter's somewhat anticipated return from the deep: I was interested that we don't actually get details on how Walter survived a shipwreck, and what we do get is conveyed in Cuttle's bare-bones story which serves to clue-in Florence to Walter's appearance, first through the illustrated shadow on the wall. I'm interested also in another reversal: Florence's proposal to Walter. Presumably her superior class station trumps gender here.

The final chapter, back at the Dombey domicile, marks this scene and tone shift with the use of the present tense, and with wry narratorial addresses, something we've seen often in the novel. The concluding line, "Mr Dombey and the world are alone together," accentuates the ironic treatment of solitude and isolation we've commented on.

Next week: #17, chaps. 52-54.

Please spread the word about Drood and "Mousehold Words"--every other week starting mid October!

Yours in seriality,

Susan

01 September 2008

Dombey #15 (chaps 46-48) December 1847

Dear Serial Readers,

Julia's comments about Carker's "lynx-eyed vigilance" remind me of the opening of this number (where that phrase appears). The first chapter--later titled "recognizant and reflective"--also underscores that Carker's sharp vision has its blind spots: deep in his own reflections riding about the city, he fails to take note of "the observation of two pairs of women's eyes." While we readers see the immediate effects of Carker's seduction of Edith (rendered via Florence's vantage point), we also see that there may be a revenge plot afoot by Alice Markwood, who has been established as a kind of mirror image of Edith. That Carker's power over others, especially women, may have its come-uppance, this along compels me to read on!

I found the middle chapter where Edith descends (and falls as a fallen woman) on the Dombey staircase a variation on melodrama, or even a precursor to sensation fiction, with lots of high drama and suspense as Florence senses something very very amiss. Yes, Dickens seems fond of the staircase trope, as we readers find in his later novel HARD TIMES.

But what was most intriguing to me in this installment is the lengthy narrative intrusion near the start of chapter 47, where Dickens dismantles any sturdy distinction between "natural" and "unnatural" in the context of the disintegrating Dombey marriage, and at the brink of Edith's elopement. Dickens's treatment here of sinfulness, corruption, and human nature seemed to me a strong echo of SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND EXPERIENCE, so much so that I almost expected some mention of Blake. But did Victorians read Blake? Take these lines, for instance: "Then should we stand appalled to know, that where we generate disease to strike our children down...infancy that knows no innocence, youth without modesty or shame, maturity that is mature in nothing but in suffering and guilt, blasted old age that is a scandal on the form we bear. Unnatural humanity!" Like the use of present-tense passages and chapters, this intervention seems another strategy to connect with readers in a tale about isolation that we read in solitude, although collectively (as Julia has pointed out).

'Tis the season (not December, when this number first appeared, but September, when the semester calendar resumes), so my posts will be shorter. But I'd like to continue with this serial readers blogging, even so! Should we read DORRIT or DROOD next? Let me know if you have a preference for shorter or long. But in any case, let's switch to a biweekly schedule.

Does anyone know if DOMBEY was ever adopted for stage or screen?

Until next week's #16 (chaps 49-51)--

Serially yours in September,

Susan

Julia's comments about Carker's "lynx-eyed vigilance" remind me of the opening of this number (where that phrase appears). The first chapter--later titled "recognizant and reflective"--also underscores that Carker's sharp vision has its blind spots: deep in his own reflections riding about the city, he fails to take note of "the observation of two pairs of women's eyes." While we readers see the immediate effects of Carker's seduction of Edith (rendered via Florence's vantage point), we also see that there may be a revenge plot afoot by Alice Markwood, who has been established as a kind of mirror image of Edith. That Carker's power over others, especially women, may have its come-uppance, this along compels me to read on!

I found the middle chapter where Edith descends (and falls as a fallen woman) on the Dombey staircase a variation on melodrama, or even a precursor to sensation fiction, with lots of high drama and suspense as Florence senses something very very amiss. Yes, Dickens seems fond of the staircase trope, as we readers find in his later novel HARD TIMES.

But what was most intriguing to me in this installment is the lengthy narrative intrusion near the start of chapter 47, where Dickens dismantles any sturdy distinction between "natural" and "unnatural" in the context of the disintegrating Dombey marriage, and at the brink of Edith's elopement. Dickens's treatment here of sinfulness, corruption, and human nature seemed to me a strong echo of SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND EXPERIENCE, so much so that I almost expected some mention of Blake. But did Victorians read Blake? Take these lines, for instance: "Then should we stand appalled to know, that where we generate disease to strike our children down...infancy that knows no innocence, youth without modesty or shame, maturity that is mature in nothing but in suffering and guilt, blasted old age that is a scandal on the form we bear. Unnatural humanity!" Like the use of present-tense passages and chapters, this intervention seems another strategy to connect with readers in a tale about isolation that we read in solitude, although collectively (as Julia has pointed out).

'Tis the season (not December, when this number first appeared, but September, when the semester calendar resumes), so my posts will be shorter. But I'd like to continue with this serial readers blogging, even so! Should we read DORRIT or DROOD next? Let me know if you have a preference for shorter or long. But in any case, let's switch to a biweekly schedule.

Does anyone know if DOMBEY was ever adopted for stage or screen?

Until next week's #16 (chaps 49-51)--

Serially yours in September,

Susan

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)