Dear Serial Readers,

Once again, time caught my attention as I read this number. The middle chapter makes a clear shift to the present tense for the first few pages (253-56) as it describes that weird temporal state of bereavement, in this case for the Dombey household following Paul's death. Time warps, one's perception of time seems strangely suspended, and Dickens captures this beautifully with verbs and participles. The first paragraph of the chapter concludes: "It seems to all of them as having happened a long time ago; though yet the child lies, calm and beautiful, upon his little bed." There are also many details about rituals surrounding death including the closed shutters at the offices in the City, the funeral procession with the black horses and feathers, as the carriage moves from the house to the church to the graveyard. Before switching back to the familiar world of past-tense narration, this section concludes with a recognition of the weird juxtaposition between ordinary diurnal life and "vast eternity" (or timelessness) which must somehow patch the unfathomable void left by Paul's death.

Then in the final chapter that relays a different kind of departure, Walter's for Barbados, the oddness of time, or keeping time, comes up again, here with references to Uncle Sol's "relentless chronometer" (286) and to Captain Cuttle's silver watch that mistells time, but this can be adjusted by regularly moving the hands backwards. These two different references to time, to the strangeness of time when someone dear dies, and to the practical difficulties of keeping time, reminds me of our earlier discussion about serial readers's bifurcated sense of time: the narrative time, the way time works (or gets derailed) within the numbers and the periodical release of these installments that insures the interruptions of "real" time beyond the pages of the novel. How do you experience time as serial readers? Does this novel seem to accentuate time more than other Dickens novels, other Victorian novels, or is this only more apparent because of the timely way we're reading it?

I'll leave to others to remark on the father/daughter divide, Dombey's blindness about Florence as his "child" because she is not the "Son" (the bit about the inscription of the grave and her coming into his room at night). Florence we learn is all of 13 now, although she's been installed in a marriage plot since Walter rescued her on the streets of London at age 6. And what about that shoe fetish, Walter?

Number 7 (chaps 20-22) for Monday July 7th, and we'll try for a weekly reading from then on. I'm hoping more people can chime in, now that we're slowing down our reading time....

Yours in serials,

s.

5 comments:

The contrast of intent and outcome is so well presented in many scenes, but an wonderful example is found here is the intent of Capt. Cuttle as he mentions to Carker that Walter and Flo may be a good pair -- thinking he is "doing a little business for the youngsters" and securing good treatment for Walter -- and having the opposite effect upon Carker, who himself has designs on Flo and so sees to it that Walter is banished. The reader is trusted to see this clearly, and of course readers love to be trusted with confidential information.

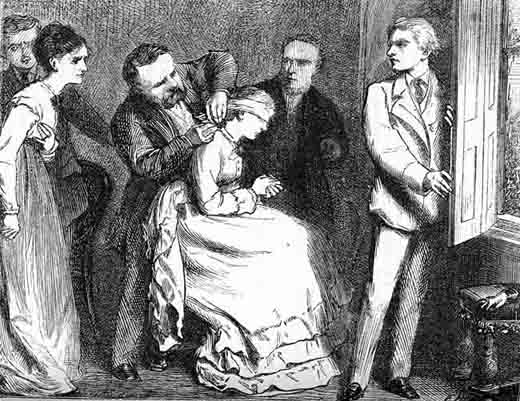

The description of the dog Diogenes establishes him as an unforgettable character. What a challenge and a treat for an illustrator to attempt a drawing that is true to those paragraphs.

I'm sure it is my age and a modern sensibility that tempts me to become impatient with Florence's futile attempts to gain her father's attention. After all, where could she have obtained the self confidence that steeling herself to his frigidity would require? She also appears clueless to Walter's body language and endearing words and presumes to pronounce their relationship as that of siblings only. I want to be on Florence's side (Dicken's desired outcome), but this section tries that intent.

The temporal shifts in this installment did stand out for me, especially the disorienting present tense that opens Chapter 18. I think the break in reading (which was much more noticeable for me with the new schedule) did make me more attentive to the text's temporal cues. Time is always evading the reader in this installment, as we shift between past and present, to strict chronometer time, to Captain Cuttle's looser watch time, to the open-ended time of Walter’s journey and Florence’s isolation.

In a way, these temporal instabilities seemed perfect for the crumbling world of Dombey and Son, just shaken by the death of little Paul and the uncertainty of Walter's voyage. With the exit of Walter at the end of the installment (the second "Son and Heir" sailing out of the picture), and Florence's relationship with her father still frozen, it's hard for the reader to see how the narrative will go on at all.

I was also interested in the characters’ relationships to their material surroundings (and other objects) in this particular installment. Both Florence and Walter have strong attachments to their own rooms, and both dread the idea of their being empty or occupied by someone else. Florence is drawn to her own chamber during her bereavement notwithstanding the painful reminders of her beloved brother, and it is particularly painful for her to think of Paul's rooms as "empty and dreary" (206). Walter also dreads leaving his room, and seems disturbed by the idea that it might have other inhabitants who "change, neglect, [or] misuse it" (218). These rooms seem to have a life, and to need their inhabitants (at least in their inhabitant’s minds). Is this a symptom of a world in which meaningful human relationships are very few and far between? Is there such a dearth of love that lonely characters like Florence (and to a lesser degree Walter) are forced to project their emotions onto their material surroundings?

I felt that this longer break really did give me more of the experience of serial reading that the novel's first readers had. I was able to do some additional reading in the interim, and when I came back to Dombey, unpressured (although I read the entire part in one sitting), I felt that I was comfortably returning to an old friend.

As I read this novel, I'm continually reminded of an essay I read in graduate school by Dorothy Van Ghent, "The Dickens World: A View from Todgers.'" It's been many years, but as I remember the essay it examines the world of animated objects and disjointed bodily parts that make up so much of Dickens's narrative. I find, at this point in my life, at least, that this works best in small doses, so I particularly appreciate the part-by-part reading.

Concerning time in this novel, I, too, was struck by the present tense interlude, which at first reminded me of the Lady Dedlock sections in *Bleak House,* all of which, if I remember correctly, are in the present tense. There, however, the eternal present provides a portentous note, almost a kind of sarcasm about Lady Dedlock, her past, and her fate. Here, as Susan wrote, it very poignantly conveys the out-of-time experience of deep grief. I was also fascinated by the fact that the description of Paul in his bed and the funeral appears after we've learned of subsequent events, but in the present tense--truly a dislocating experience.

As for Florence, I found it very believable that she would continue to seek her father's love and connection. We know that even severely abused children crave their parents' love and continue to believe they will someday receive it. I was relieved to see that after her father's (seemingly clueless) dismissal she picked herself up and went to say good-bye to Walter--even if she does think of him at this point as a brother. She needs a loving family member, and she is only 13; he seems to be several years older.

I'm getting to this a little late, and so I don't really have all that much to say about the content of this number, but I do think that this experience has taught me something valuable about Victorian narrative. This leisurely pace through the novel is completely different from the two other types of reading I'm used to -- namely the grad school "sprint through the text" or the pleasure reading "squeeze it in whenever you can or wish" methods. And as such I'm finding myself much less concerned about slower-paced installments. I like mj's comment above about "returning to an old friend"; at this relaxed speed, the looseness and bagginess of this loose baggy monster seems like part of the novel's charm.

One quick comment on the novel itself -- we're introduced to more personified objects in the last chapter, and one of them is the "chronometer." It joins the clock Paul listens to as a time-related object that gains a strange form of activity and life. At first I'd simply been chalking this personification up to a recurring Dickens motif. Bleak House features personified objects about halfway through to build suspense around a murder, and Our Mutual Friend has a character reduced to a dining table. Is there anything significant about the fact that the objects here are related to time?

The aspect of this number I found most striking was the parallelism between the Sol/Walter and Dombey/Son relationships.

Sol says: “I would rather have my dear boy here. It’s an old-fashioned notion, I dare say. He was always fond of the sea. He’s glad to go.” The most straightforward echo here is the use of the word “old-fashioned.” Similarly, Walter “was always fond of the sea” just as Paul was always listening to the sea and watching it. Further, where Sol calls Walter “glad to go,” Paul was at least ready to go or resigned to go to his death.

But the most poignant parallel is how the men differ in their relationships with their boys. While Sol wants a good future for Walter of course, it will break his heart not to share the living present with him. Walter is acutely aware of that, and this awareness is at the center of his anxiety about leaving Sol.

In contrast, Dombey sees Paul’s childhood as something to get through pending the arrival of what’s really important, his young manhood. This point is made repeatedly in the pre-Brighton chapters and then recalled during the Blimber period where Dombey decides he needn’t have the Sunday visits with the children anymore. Because Dombey put no value on Paul’s childhood (which is all Paul ever had), it could be argued that Paul never really existed for him at all.

Walter’s farewell to his room also echoes Paul’s farewell to the halls of Blimber.

The entry of Florence into the Walter/Sol relationship deepens the echoes and contrasts. She notes that Sol “is going to be left alone, and if he will allow me—not to take Walter’s place, for that I couldn’t do, but to be his true friend and help him if I ever can while Walter is away, I shall be very much obliged to him indeed.” Thus, what she wished for at home—to bond with her father over the lost son and brother—she obtains at the Midshipman’s—bonding with the surrogate father over the lost surrogate son and brother.

And, of course, Captain Cuttle promotes this surrogacy in a different sphere, in his over-optimistic interview with Mr. Carker. I experienced this as the single most painful episode in the book, Yes, I found this more painful than the deaths, in that excruciating and mortifying “I Love Lucy” “Honeymooners” kind of way.

Relatedly, Walter sails off in the none-too-subtly named “Son and Heir.”

Post a Comment