Dear Serial Readers,

Yes, I certainly do look forward to my weekly reading portion (to reply to a comment from last week). I think this leisurely pace allows me to notice so much more along the way--lots of trees, even if a wider scope of the forest is sometimes harder to see than a quick, compressed reading might yield.

This number, after the revue/review of the last one, has the coherence that I've noticed with each installment. Again too, we are introduced to new characters, two women who seem mirror opposites, much like Florence (the good angel) and Edith (the fallen, desperate or despairing angel): Harriet Carker and Alice Marwood. And of course the finale underscores binaries and their undoing (the "many circles within circles" of the narrative) where the "high grade" mother/daughter dyad (Cleopatra and Edith) and the "low" version (Good Mrs Brown--although there's quite a bit of uncertainty about her name in this chap--and Alice) dovetail, or as Dickens puts it, "the two extremes touch" (Oxford 525).

Thematically this installment coheres around loss and gain, fallenness and (at least the hope of) redemption or restoration. Here we have the first chapter, about Captain Cuttle taking in the newspaper item that strongly indicates that Walter has drowned at sea (although we know enough to suspect this loss as final); the second chapter, about Harriet Carker's encounter with Alice, the fallen woman returned from the penal colony of Australia, and then the last chapter, about the lost daughter restored to her mother, much as this restoration isn't all sweetness and light.

I'm most struck, though, with Dickens's portrayal of Alice's rage and resistance. First, her refusal of customary moral redemption as she challenges Harriet, "Why should I be penitent, and all the world go free?...Who's penitent for the wrongs that have been done to me!" (Oxford, 510).

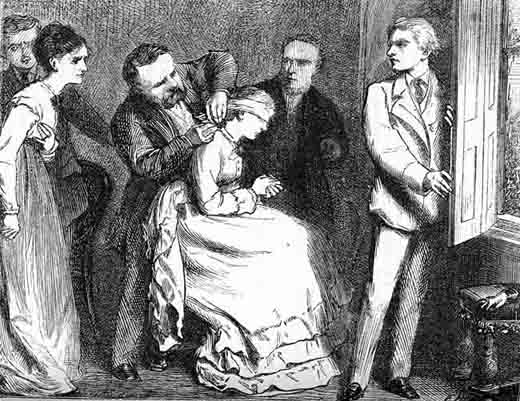

Then there's her return to her mother where she tells her life story, from "a child called Alice Marwood" to a "girl called Alice Marwood" to a criminal called Alice Marwood"--a story that echoes Edith's sardonic version to her mother, where enforced marriage or prostitution is simply a matter of class position. And finally, Alice spurns Harriet's charity, given further emphasis by the illustration (with the caption, "The rejected alms").

The potential of these two "fallen" women (Alice and Edith) overlapping and even encountering each other is set in play because of the Carker connection--and the suspense grows and grows! I can see how having to wait for the next installment intensifies the suspense. Does this delayed gratification make the desire for narrative fulfillment more thrilling?

See this link on Dickens and Urania Cottage, the home for "homeless" (or "fallen") women that Dickens began to support around the time he was writing Dombey. You'll find references to other fallen women in Dickens's novels, but no mention of this particular one.

And guess what? It's August, and this number was first published and read in August (some 161 years ago)! How's that for skewed simultaneity? And with the next installment, we've completed a full year's cycle of numbers, from October 1846 to September 1847.

Next time: number 12, chaps 35-38---four shorter chapters instead of the more habitual three.

Serially,

Susan

2 comments:

A couple of thoughts from me -- I keep seeing an overlap between Carker and Bleak House's Tulkinghorn. Both are malevolent servants of flawed (but not evil) men. Both possess a lot of knowledge that can threaten wives of their masters. And both have a picture in their house that's invested with major significance (although this one seems to be functioning on a literal level, Edith's resemblance, rather than the symbolism of Tulkinghorn's Allegory and its pointing finger).

I was also struck by all the characters that don't appear in this month's reading: Dombey, Edith, Florence, "Cleopatra," and so on. It's very interesting to me that so much time can be spent on a set of characters -- Mrs. Brown and the extended Carker clan -- who seemed at first to play such minor roles here. And, in a testament to just how massive this novel is, we get a new and seemingly important character, Alice, over five hundred pages into the book. Dombey and Son continues to add plots and characters at a point many novels don't come close to reaching.

Just a few comments on another fascinating reading. First, a question: Are we certain that Alice had been transported to Australia? It crossed my mind that perhaps she had been transported to an island in the Caribbean, and is somehow a refugee from the shipwrecked Son and Heir--perhaps on its return voyage. I have not read ahead (so don't know if this surmise is correct or not), and if I've missed a clear Australia reference, please let me know. But (possibly because of her wet, rain-soaked garb) I connected her with the shipwreck--metaphorically, too, I suppose.

I also thought a great deal about the issue of sentimentality, a charge that is often leveled at Dickens. I considered that some might think Captain Cuttle's reaction to Walter's apparent death is sentimental, but I'd disagree. After referring more than once (I think) in these blogs to Capt. C as a caricature, I found my first impressions overturned in the long first chapter of part 11. I was extremely moved by his catalog of losses in Walter's death--Walter as a child, a youth, etc. This is akin to what a parent might feel as a child grows up (in fact I've read an early 20th c. essay on the subject, by a parent). We see a parent's tenderness in this expression of grief by Captain Cuttle, now considerably more than an avuncular figure. His religiosity and devotion to ersatz biblical texts and the Book of Common Prayer, treated with humor especially before the wedding, now takes on more depth and poignancy as he in fact performs a burial service for Walter, who has supposedly drowned alone and friendless in the Atlantic.

It occurred to me as I began reading Alice Marwood's story that perhaps here was the true sentimentality, the conventional treatment of the fallen woman, but of course, as Susan points out, we quickly learn that Alice is hardly the sentimental stereotype. I thought about the narrator's comparison of the two types of prostitutes, Alice and Edith, and could not help thinking that Edith still has it better. Dickens here seems to refuse to acknowledge the advantages of class in his concern with universal human feelings. (This may be yet another parallel to Bleak House.)

Finally, Carker becomes ever more fascinating. His scenes provide a welcome enveloping chill in August.

Post a Comment