Dear Serial Readers,

I'm going to write something very short right now and look forward to your thoughts on this installment. Everyone has such fantastic observations. Alicia's makes me think of the particularly anachronistic flavor of the narrative, and, as she points out, how Eliot weaves in this blurring of times into a descriptive passage.

What did you think of Savonarola's debut at Fra Luca's (Dino's) deathbed? I was struck by his "rich, strong voice" as a very physical presence for Romola. And what did you think about Fra Luca's vision, or, foreshadowing as inspired prophecy? How will this prophetic vision shape the narration as it continues? The use of prophecy suggests another kind of temporal blurring. There's much much more--so, your thoughts on this installment?

I will be traveling without my computer from June 19-July 5, so I'd like to propose some catching up time for all of us. The fifth installment is chapters 21-26, and that's what I'll post on the week of July 6th. I hope we'll all be.... on the same page by then!

Serially soon,

Susan

3 comments:

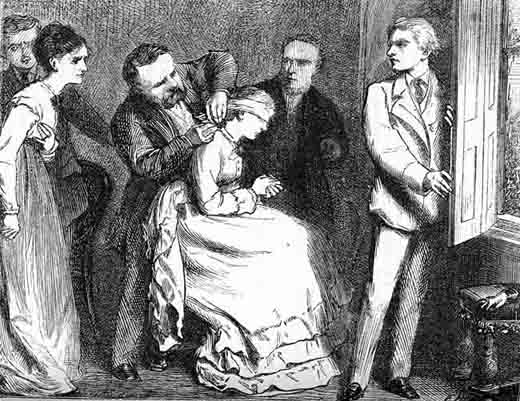

I realize I hadn't been noticing the form of each installment, so I spent time thinking about the form of #4, and it is highly structured. Chapter 15 begins with Romola walking into the dimness of San Marco to hear her brother's dying words, especially his vision. Chapter 20 ends with Tito and Romola leaving the wedding church into a dim outside, and with Tito promising Romola that "when we are in the light" she will forget the visionary pageant she has seen in the streets of Florence after the wedding and she will from now on be "with her Care-dispeller."

The pageant in the street recalls her brother's vision, with the dead following her as a bridal train. Indeed, the vision starts to seem literal rather than figurative with the arrival of the pageant including "what looked like a troop of the sheeted dead."

I also wonder if Chapter 20 somewhat combines the serious and visionary tone of Chapter 15 with the Florentine idea of humor and spectacle of Chapter 16.

Susan's question about Savonarola and how we feel about our first encounter with him is intriguing, also. It seems to me so far that the novel does not present him as a clear villain, which I find intriguing. But perhaps that is due to my lack of understanding of Eliot's view of Catholicism.

What really struck me in this installment (and brought me back to the previous one) was the interconnected importance of three objects, Tito's ring, Luca's crucifix, and the tabernacle created by Piero di Cosimo.

Baldassare's ring, given to Tito to wear as soon as he was big enough, is obviously a symbol of the older man's love and hope for his adopted son. Luca's crucifix represents both himself and his faith, as well as his vision of T&R's wedding. He gives it to Romola to remind her and connect her with all three things, perhaps most importantly the vision.

Tito cavalierly casts off the ring in his moment of fear. He spends a lot of time rationalizing about this, and of course it's interesting that the main disadvantage he sees in the sale is that other people will notice the ring’s absence and disapprove. Romola both fears and treasures the crucifix, giving it pride of place on her mantelpiece.

In the bizarre device of the tabernacle, Tito unites the other two objects. He pretends that he sold the ring in order to buy the box, and what's the box for? To hide the crucifix--the thing itself and (he hopes) what it represents. Hidden, can it still be Romola’s "beacon in the darkness," as Savonarola had suggested?

The ring as symbolic object goes off in another direction as well. Tito has sold one ring to assure his grasp of another--the ring of betrothal. The exchange of rings, we learn, is one of the events at the betrothal ceremony (Chapter 20). This harkens back to Tito and Tessa's faux marriage. Tessa says: "madre wears a betrothal-ring." Tito: "you must not wear a betrothal-ring, my Tessa, because no one must know you are married." (Chapter 14).

Tito’s creation and use of the tabernacle is a strange solution for his problems with the ring and the crucifix. His choice of decoration is truly bizarre. The use of pagan imagery to cover a repository for a crucifix is odd to begin with. But, with all the lovers of classical mythology to choose from, why choose Bacchus and Ariadne to symbolize the newly-betrothed? Ariadne was the girl who betrayed her father King Minos by showing Theseus how to defeat the Minotaur (whom Minos had been nourishing with Athenian youth). Surely, we can only cheer at this betrayal, but isn’t this a strange counterpart for the filially devoted Romola? After the death of the Minotaur, Ariadne ran off with Theseus, who jilted her, but, not too worry, along came the lusty Bacchus. At least in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Tito’s probable source), there’s no more to that story.

Meanwhile, we learn that Piero captured Romola’s image by using her as a model for Antigone. Antigone?! Antigone was one of the offspring of Oedipus and Jocasta, so clearly another girl with Daddy issues. Plus, Sophocles’ play of her name is all about her efforts to get a proper burial for her brother Polyneices. Creon refused a proper burial because he considered Polyneices a traitor. Echoes of Romola, Bardo and Luca here.

A satisfying read for an ex-Classics major!

A fantastic painting of Ariadne and Bacchus (with, as I recall, Theseus retreating in the background) is at London’s National Gallery, and I’m sure can be seen online.

To piggy-back off of Maura's post about the tabernacle created by Piero di Cosmo, it also seems that the crucifix within a box (a "beacon in the darkness" that is shut out from sight) mirrors the position of the radiant and virtuous Romola within the cold walls of her father's house. At least before her marriage, Romola is hidden away, just as the crucifix is. In my mind, this raises the question of whether she's moving in an inverse direction--will she come out into the open after the marriage?

I've been thinking about why this seems (at times) like a more difficult novel to get into, and I wonder if it is in part because Romola is so cloistered (both literally and in terms of the access the narrator gives us to her). So far, we've been privy to Tito's thoughts in detail--his interior world--but Romola's interior world has been more elusive. Eliot adopts this same approach of delayed attention to the title character in Daniel Deronda, and I wonder whether this is a particularly useful strategy for serial fiction. Does the "mystery" of the title character, and the suspense of finally understanding why the title was chosen, keep us reading?

Post a Comment