Dear Serial Readers,

Julia's comment makes me see some affinities between the world of crime, money, corruption in this novel and in more recent serials like The Wire, and the connections across social class and institutional divides. Yes, the remaining mystery--saved up for the double-number finale (next week!)--is the unraveling of Mrs. Clennam's money-related crimes, and the nature of "the commodity" Blandois had offered to sell to her. I'm also a first-time reader of this novel, so I can only speculate. But I suspect this secret around the Clennam household will go far in explaining many of Arthur's early questions when he first returned to London at the start of the novel. Maybe he and Amy are half-siblings, although I think that's far-fetched! Still, in the spirit of wild speculation! There is a tightening of the scene and action in these last installments too--these three chapters set in Marshalsea, and the last five, at least according to their titles (Closing in, Closed, Going, Going!, Gone)all plot-driven around resolutions.

I was also thinking there are different kinds of avarice at work in this novel. Obviously there's plenty of money-greed. But there's people-greed too (even self-greed), and here Amy Dorrit's overwhelming determination to sacrifice herself to a father/figure (now, Arthur, who continues to call her "my child") is a prime example. But like the range of money mishaps and crimes, there seems to be good and bad forms of this personal avarice. Young John is another stellar example--he knows Amy is in love with Arthur and his struggle to quell his jealousy by telling Arthur suggests the good kind of people-avarice. Young John's gravestone fantasy ending with the cap-fonted "MAGNANIMOUS" humorously announces that such self sacrifice might also desire recognition. I loved that tombstone inscription--in part because it provides another angle on what appears to be Amy's selfless devotion. In other words, this seeming self abnegation might not be so purely selfless after all. With so much giving, there's the pleasure one takes in that form of virtue. Now Mrs. Clennam seems the wrong kind of avaricious person and I suspect we'll learn more about that in the concluding chapters. There are the in-between comic kinds too, like Fanny.

Next week--all the rest! How many of you have truly played by these "Serial Reader" rules and *not* yet finished the novel at this point? It is a different kind of reading experience, isn't it, to move in small and steady increments like this?

Starting the week of July 26: The Moonstone!

Serially speculating to the end,

Susan

8 comments:

I really haven't finished yet! And I don't remember the ending at all from when I saw the film in '88 or so. All I remember was her father's belief that he was in prison.

I have only read the chapter titles, and I wonder what is "gone." Perhaps an auctioning of Little D's hand?

Intention also seems to matter in how much the novel condemns the actor--it seems clear to me that Mr. Merdle intended to swindle people, but then it's unclear to me what he expected to happen--it would last forever?

I am not liking the novel more, but I'm admiring it more and more. This section was so claustrophobic, all inside the Marshalsea, and I found it so frustrating! No doubt much less frustrating than Arthur did, however.

I was a bit irritated with Ferdinand Barnacle stopping by--it seemed a bit off of the tone of the rest of the Barnacle presences, but I did enjoy when Arthur hopes that Mr. Merdle and "his dupes" will provide a useful warning for the future, and Ferdinand laughs that off, "The next man who has as large a capacity and as genuine a taste for swindling, will succeed as well." It made me think of Susan's post from last week and memories of much more recent swindles!

I was a bit confused by Arthur's mother's note: what else could he ruin? And I'm always confused by John the Baptist's treatment of Blandois/Rigaud--why does he continually serve him? It's a fascinating commentary, perhaps, on what it means to be a gentleman--compare the wonderful Plornish family. And, yes, the MAGNANIMOUS John Chivery, who in the satisfaction of that magnanimity is able to live a long life rather than dying early of a broken heart as in his earlier gravestones.

I was also impressed by the low key way in which Little Dorrit (egad, her "right name") and Arthur express their love for each other--a scene which would be a climax in so many novels is, well, a bit melodramatic, but also so quiet. Yet it's hard to see her be such a servile daughter--the highest form of love! Sigh. (and another, more heartfelt sigh, as I think of how painful such a form of love would be to *me*, and how hard I've tried to avoid it!)

I'm so excited to solve the final mysteries, and to get Arthur and Amy home to their warm little hardworking home where I expect them to end up!

I really haven't finished yet! And I don't remember the ending at all from when I saw the film in '88 or so. All I remember was her father's belief that he was in prison.

I have only read the chapter titles, and I wonder what is "gone." Perhaps an auctioning of Little D's hand?

Intention also seems to matter in how much the novel condemns the actor--it seems clear to me that Mr. Merdle intended to swindle people, but then it's unclear to me what he expected to happen--it would last forever?

I am not liking the novel more, but I'm admiring it more and more. This section was so claustrophobic, all inside the Marshalsea, and I found it so frustrating! No doubt much less frustrating than Arthur did, however.

I was a bit irritated with Ferdinand Barnacle stopping by--it seemed a bit off of the tone of the rest of the Barnacle presences, but I did enjoy when Arthur hopes that Mr. Merdle and "his dupes" will provide a useful warning for the future, and Ferdinand laughs that off, "The next man who has as large a capacity and as genuine a taste for swindling, will succeed as well." It made me think of Susan's post from last week and memories of much more recent swindles!

I was a bit confused by Arthur's mother's note: what else could he ruin? And I'm always confused by John the Baptist's treatment of Blandois/Rigaud--why does he continually serve him? It's a fascinating commentary, perhaps, on what it means to be a gentleman--compare the wonderful Plornish family. And, yes, the MAGNANIMOUS John Chivery, who in the satisfaction of that magnanimity is able to live a long life rather than dying early of a broken heart as in his earlier gravestones.

I was also impressed by the low key way in which Little Dorrit (egad, her "right name") and Arthur express their love for each other--a scene which would be a climax in so many novels is, well, a bit melodramatic, but also so quiet. Yet it's hard to see her be such a servile daughter--the highest form of love! Sigh. (and another, more heartfelt sigh, as I think of how painful such a form of love would be to *me*, and how hard I've tried to avoid it!)

I'm so excited to solve the final mysteries, and to get Arthur and Amy home to their warm little hardworking home where I expect them to end up!

I really haven't finished yet! And I don't remember the ending at all from when I saw the film in '88 or so. All I remember was her father's belief that he was in prison.

I have only read the chapter titles, and I wonder what is "gone." Perhaps an auctioning of Little D's hand?

Intention also seems to matter in how much the novel condemns the actor--it seems clear to me that Mr. Merdle intended to swindle people, but then it's unclear to me what he expected to happen--it would last forever?

I am not liking the novel more, but I'm admiring it more and more. This section was so claustrophobic, all inside the Marshalsea, and I found it so frustrating! No doubt much less frustrating than Arthur did, however.

I was a bit irritated with Ferdinand Barnacle stopping by--it seemed a bit off of the tone of the rest of the Barnacle presences, but I did enjoy when Arthur hopes that Mr. Merdle and "his dupes" will provide a useful warning for the future, and Ferdinand laughs that off, "The next man who has as large a capacity and as genuine a taste for swindling, will succeed as well." It made me think of Susan's post from last week and memories of much more recent swindles!

I was a bit confused by Arthur's mother's note: what else could he ruin? And I'm always confused by John the Baptist's treatment of Blandois/Rigaud--why does he continually serve him? It's a fascinating commentary, perhaps, on what it means to be a gentleman--compare the wonderful Plornish family. And, yes, the MAGNANIMOUS John Chivery, who in the satisfaction of that magnanimity is able to live a long life rather than dying early of a broken heart as in his earlier gravestones.

I was also impressed by the low key way in which Little Dorrit (egad, her "right name") and Arthur express their love for each other--a scene which would be a climax in so many novels is, well, a bit melodramatic, but also so quiet. Yet it's hard to see her be such a servile daughter--the highest form of love! Sigh.

Well, I liked this installment, from young Barnacle’s ironic hope that Arthur’s imprisonment had nothing to do with him, et. al, (“It is our misfortune to have to do that kind of thing”) to the psychology of Arthur v. Arthur, to John C’s motives. Poor Arthur. No rest for the weary. Barnacle no sooner leaves than Blandois (!) appears, then the odd little return of John.

Backing up a bit, I was surprised that Amy’s love for him, as John saw it, was news to Arthur. I wondered where Arthur’s subsequent self-awareness and inventory regarding his persistent view of Amy as a child would lead. By the end of Chapter 29, he’s damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t “love” Amy. If he bans her from the prison altogether, he misses her devotion and attention. What he truly wants seems to be dueling with his idealistic, illusory self. He tells Amy not to visit him “soon or often” in prison. To what purpose? He can’t quite live up to the image of himself who would sacrifice his own solace and tell her to get a life outside the Marshalsea and not visit him at all. (Who could? Would?) But still, he seems to need to show her he’s selfless, more selfless than is humanly possible, perhaps. Would he rather strive for illusion than be true to his real self, the one in love with the woman Amy?

I don’t quite trust John C. “Will you tell Miss Dorrit I’ve been honorable, sir?” he asks Arthur. With Arthur under lock and key, does he hope to win Amy, by default?

I read this novel last summer, but I've been playing along this time, so I haven't gotten to the final installments yet! And I'm looking forward to them. It's pretty amazing to me that the novel could take so long to reveal its big surprises -- and yet still manage to keep our interest even as some of the mysteries remain mysterious for almost eight hundred pages or so.

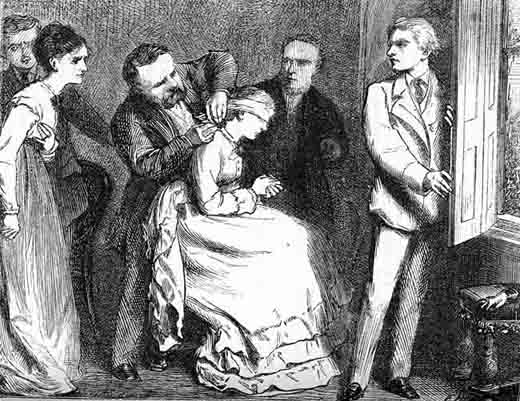

I think what struck me about this last section was the way Dickens combines sentimentality and cynicism together. Sure, the scene where Little Dorrit arrives to take care of Arthur might be read as sentimental (although I found myself invested enough in these characters and their world that I was very moved by it). But the chapters before? Barnacle confidently letting Arthur know that human greed will lead to more Merdles? The total dismissal of honest inventors like Doyce? Rigaud's claim that he represents the capitalist spirit of selling to Society (so that our two big representatives of economic power are frauds and criminals like Rigaud and Merdle)? Wow. Apparently (I don't remember where I saw this) George Bernard Shaw said that he thought Little Dorrit was a more radical book than Marx's Capital, and after reading this section I think I can see why. It's interesting that this sort of radical criticism sits right next to the love plot with Arthur and Amy. For me, the contrast almost enhances each part.

Oh, and I'm really looking forward to The Moonstone, which I loved when I read it a while back!

I too am playing by the rules of serial reading, and so I haven't finished the novel yet. I am dying to find out how everything is resolved!

I was really moved in this installment by the way Dickens captures the despair of the prisoner through his description of Arthur's adjustment (or maladjustment) to prison life. As Kari said, the novel captures the claustrophobia of the Marshalsea brilliantly.

I was also moved, but also disappointed, by the sentimental scene between Arthur and Amy. At first, I saw a hint of the Jane Eyre plot--Amy returns rich to "rescue" the debilitated Arthur, just as Jane does with Rochester at the end of Bronte's novel. This was potentially exciting. However, in Dickens’s novel Arthur *refuses* to be taken care of by Amy (although, as others noted, he doesn't release her altogether). This seemed to me to be the worst possible position for Amy Dorrit. To be told that the one you've loved from afar now realizes that the feeling was mutual all along, but it's too late because his circumstances have changed--as Amy is--seems utterly cruel (despite Arthur's good intentions). This is almost a Thomas Hardy scenario! I wonder if we are being set up for a phenomenally happy ending, one made more vivid by the contrast with this dark, cruelly emotional scene?

One final observation. I wonder if we could read Little Dorrit's offer to give all she has for a friend because ("I have no use for money," p. 787) as a kind of response to Rigaud's previous intimation that everyone in society participates in the practice of “selling friends” (p. 778). Her intervention is an attempt to break that vicious practice, but on the other hand, it is not entirely successful because Arthur refuses to view the gesture outside the terms of a monetary system ("Liberty and hope would be so dear, bought at such a price, that I could never support their weight, never bear the reproach of possessing them," he responds p. 788). Amy's rhetoric of compassion seems to come up against society's impenetrable rhetoric of monetary wealth in the phrasing that Arthur uses—“dear,” “bought,” “price” “possession.” Amy can see beyond these terms (“dear” in terms of affection rather than price), but Arthur doesn’t seem to be able to, at least not yet.

I too am playing by the rules of serial reading, and so I haven't finished the novel yet. I am dying to find out how everything is resolved!

I was really moved in this installment by the way Dickens captures the despair of the prisoner through his description of Arthur's adjustment (or maladjustment) to prison life. As Kari said, the novel captures the claustrophobia of the Marshalsea brilliantly.

I was also moved, but also disappointed, by the sentimental scene between Arthur and Amy. At first, I saw a hint of the Jane Eyre plot--Amy returns rich to "rescue" the debilitated Arthur, just as Jane does with Rochester at the end of Bronte's novel. This was potentially exciting. However, in Dickens’s novel Arthur *refuses* to be taken care of by Amy (although, as others noted, he doesn't release her altogether). This seemed to me to be the worst possible position for Amy Dorrit. To be told that the one you've loved from afar now realizes that the feeling was mutual all along, but it's too late because his circumstances have changed--as Amy is--seems utterly cruel (despite Arthur's good intentions). This is almost a Thomas Hardy scenario! I wonder if we are being set up for a phenomenally happy ending, one made more vivid by the contrast with this dark, cruelly emotional scene?

One final observation. I wonder if we could read Little Dorrit's offer to give all she has for a friend because ("I have no use for money," p. 787) as a kind of response to Rigaud's previous intimation that everyone in society participates in the practice of “selling friends” (p. 778). Her intervention is an attempt to break that vicious practice, but on the other hand, it is not entirely successful because Arthur refuses to view the gesture outside the terms of a monetary system ("Liberty and hope would be so dear, bought at such a price, that I could never support their weight, never bear the reproach of possessing them," he responds p. 788). Amy's rhetoric of compassion seems to come up against society's impenetrable rhetoric of monetary wealth in the phrasing that Arthur uses—“dear,” “bought,” “price” “possession.” Amy can see beyond these terms (“dear” in terms of affection rather than price), but Arthur doesn’t seem to be able to, at least not yet.

I too am playing by the rules of serial reading, and so I haven't finished the novel yet. I am dying to find out how everything is resolved!

I was really moved in this installment by the way Dickens captures the despair of the prisoner through his description of Arthur's adjustment (or maladjustment) to prison life. As Kari said, the novel captures the claustrophobia of the Marshalsea brilliantly.

I was also moved, but also disappointed, by the sentimental scene between Arthur and Amy. At first, I saw a hint of the Jane Eyre plot--Amy returns rich to "rescue" the debilitated Arthur, just as Jane does with Rochester at the end of Bronte's novel. This was potentially exciting. However, in Dickens’s novel Arthur *refuses* to be taken care of by Amy (although, as others noted, he doesn't release her altogether). This seemed to me to be the worst possible position for Amy Dorrit. To be told that the one you've loved from afar now realizes that the feeling was mutual all along, but it's too late because his circumstances have changed--as Amy is--seems utterly cruel (despite Arthur's good intentions). This is almost a Thomas Hardy scenario! I wonder if we are being set up for a phenomenally happy ending, one made more vivid by the contrast with this dark, cruelly emotional scene?

One final observation. I wonder if we could read Little Dorrit's offer to give all she has for a friend because ("I have no use for money," p. 787) as a kind of response to Rigaud's previous intimation that everyone in society participates in the practice of “selling friends” (p. 778). Her intervention is an attempt to break that vicious practice, but on the other hand, it is not entirely successful because Arthur refuses to view the gesture outside the terms of a monetary system ("Liberty and hope would be so dear, bought at such a price, that I could never support their weight, never bear the reproach of possessing them," he responds p. 788). Amy's rhetoric of compassion seems to come up against society's impenetrable rhetoric of monetary wealth in the phrasing that Arthur uses—“dear,” “bought,” “price” “possession.” Amy can see beyond these terms (“dear” in terms of affection rather than price), but Arthur doesn’t seem to be able to, at least not yet.

Post a Comment