Dear Serial Readers,

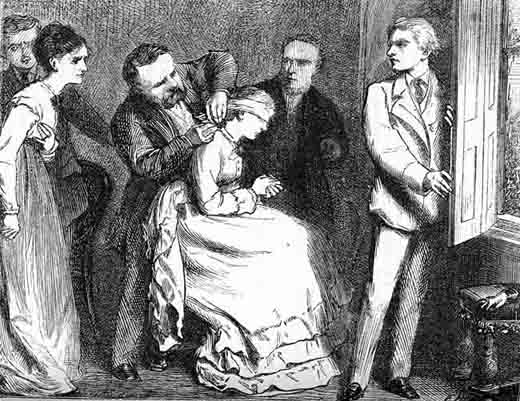

From female murderers to a High Church lawyer who has a habit of wife-beating in Eliot's final "Scene." I must say I was taken by this first installment--how we're initially introduced to Dempster's campaign against the Evangelical minister Tynan's evening lectures, and then other scenes in Milby (forerunner of Middlemarch?) replete with tea, handicrafts, and gossip, including Tynan's comment about Mrs. Dempster, aka Janet, and then finally her sad story. There's something about the form of this installment that performs the suppression of domestic abuse--until the end. All this piling up of public sphere politics, spearheaded by Dempster, and then he resurfaces at the end when he returns home, drunk, and beats Janet. Is this, like realism, or part of realism, domestic violence as ordinary or as the dirty secret everyone knows?

As Plotaholic asks about what are female murderers doing in Eliot's realist fiction, I would ask the same about the abusive husband, who has a different public face. I sometimes think Eliot uses sensational scenes (like Mme Laure or Gwendolen's held hand in Grandcourt's drowning--and do we know in either case what did cause the deaths of their husbands?)for realist ends, which could mean ambiguity, lack of resolution or full disclosure--an ending that doesn't quite conclude. It's interesting that both *Middlemarch* and *Daniel Deronda* prompted sequels.

I found moving the last paragraphs of this segment on the twin paintings over mantelpieces, one of Janet's mother, the other (Christ about to be crucified?) by Janet as a young girl, as symbolic presences of mother and martyred daughter to each other. Yet neither is able to actually speak about this horrible secret of Janet's abuse. Like Janet's mother, and Milbyites who seem to know what's going on here, the reader too can feel, but cannot do anything. I'm hoping Tynan does.

One more thing--I wonder if the "Janet" mentioned in the first chapter of the first story of Amos Barton is the same "Janet" here? Perhaps just a coincidence? Mr. Gilfil does come up in that first chapter of "Amos," and I'm suspecting that there are more networked connections across these three "Scenes."

Next week: chapters 5-9.

Serially stunned,

Susan

1 comment:

I enjoyed Susan's comments on this installment! I noticed that the first chapter has all the anti-Tryanite sentiment, but I had no idea who Tryan was until the second chapter.

I admit that I did not like the switch in tone to what seemed to me maudlin, on the narrator's part, in the scenes of abuse. The tone does keep the focus of the scene away from the violence, however, and on the sorrow.

I also noted that the narrator identifies himself as male, when he recalls what he felt when he was in coat-tails for the first time and he feared the young ladies were sarcastic toward him. Is that why he takes on the sarcastic tone so thoroughly himself as he tells his stories of his childhood town?

I did enjoy the discussion over the origin of "Presbyterian," and was suitably horrified that Mr. Dempster, so insistently wrong in that discussion, represents the intellect of the town. They just needed a smart phone.

My edition with the photos is Houghton MIfflin Warwickshire Edition of the Writings of George Eliot from 1907. The photos in this story are exclusively of outdoor locations.

Post a Comment